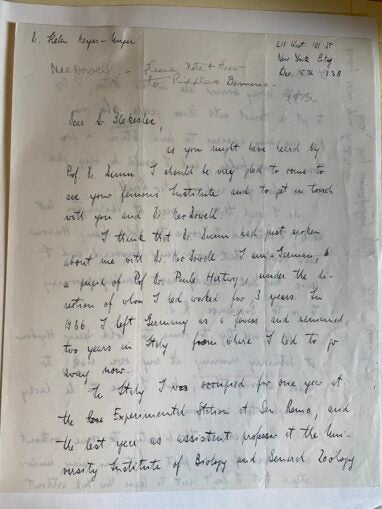

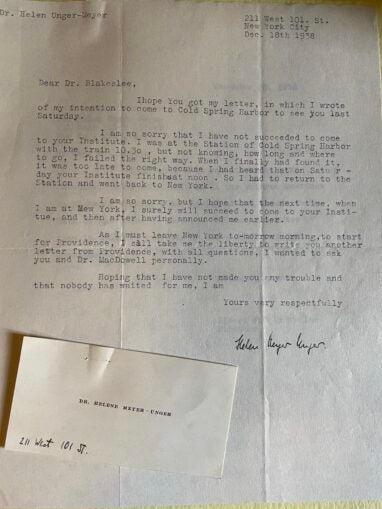

In December of 1938, Dr. Helene Meyer-Unger wrote to Albert Blakeslee, the director of the Carnegie Institution’s Department of Genetics at Cold Spring Harbor. She was in New York City and wanted to come and visit the lab and meet Blakeslee and some of the other researchers there. Meyer-Unger described herself as “a German…In 1936 I left Germany as a Jewess and remained two years in Italy.” In Italy she had worked at the Experimental Station at San Remo, “and the last year as an assistant professor at the University Institute of Biology and General Zoology at Milan.” Forced to leave Italy, probably as a result of the anti-semitic laws passed by the Fascist regime there in 1938, she had arrived in the United States and was now looking for a position in her field.1

Meyer-Unger was one of many German Jewish scholars who fled Europe for the United States in the 1930s. By 1940, between 1000 and 1500 university professors had left Germany and Austria. If you include more junior scholars and research scientists unaffiliated with universities, the number is closer to 2000. Most of these scholars were Jewish or had one Jewish parent. Some were not Jewish but were persecuted for their political convictions.2

Historians have traced the biographies and later careers of these scholars.3 Those who came to the United States faced an academic culture steeped in subtle anti-semitism that characterized Jews as pushy, ill-mannered and grossly individualistic — that is, they were imagined to be a contrast to how upper-class Protestant scholars saw themselves. The Cold Spring Harbor archives offer an example from the 1910s of precisely this kind of anti-semitism in action. Charles Davenport, then director of the Biological Laboratory and the Carnegie Institution’s research station at Cold Spring Harbor, was asked for a recommendation of Sidney I. Kornhauser, a former student who had gone on to an academic career. Kornhauser was Jewish, and this had come up in the context of his candidacy for a job. Davenport professed himself surprised that anyone would hold it against Kornhauser that he was Jewish, since

he didn’t boast about it [being Jewish] or rub it in the way some Jews do…I think his middle name is ‘Israel.’ I have seen a good many Jews in my day and have had a good many at the Biological Laboratory. If they were all like Kornhauser there wouldn’t be the prejudice that there seems to be among many people about them. I must confess I have it rather strongly myself since I have met a good many of the other kind…Kornhauser comes from Pittsburgh and they seem to have some pretty good Jews there.4

Despite the hardships imposed by their status as refugees and the discrimination that Jews had traditionally faced in the American academy, many members of this cohort of scholars were very successful. The skills and expertise that they brought with them proved valuable for the war effort, and many academics who had previously espoused views like those of Charles Davenport began to change their minds. By the 1940s, these displaced scholars were increasingly seen as an asset to the academy and to the nation.5

We do not have any further documentation about Helene Meyer-Unger in our files. We know that her planned visit to Cold Spring Harbor did not work out, since she arrived on a Saturday afternoon when the laboratory was closed.6 We do know, though, that Blakeslee read her initial letter and that he wrote a note to Edwin Carleton McDowell, asking him to take a look at the letter and then show it to Oscar Riddle and Milislav Demerec (all three were colleagues at Cold Spring Harbor). She included her card with her letter, and on the back someone at Cold Spring Harbor noted that she “seems like a well-trained person in cytology and genetics.” If anyone has come across information about her either before or after 1938, please contact us! We’d be excited to find out more about her story. The CSHL Archives can be reached here on Twitter @cshllibrary or via email at archives@cshl.edu.

The archival material in this post comes from the Carnegie Institution of Washington Collection at the CSHL Archives. Find out more about the collection here.

Notes

[1] Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Archives, Carnegie Institution of Washington collection (abbreviated CIW) Box 9, Folder: Blakeslee, A. F. 1938 (July-December) Meyer-Unger to Blakeslee, Dec. 15, 1938. [2] Marjorie Lamberti, “The reception of refugee scholars from Nazi Germany in America: philanthropy and social change in higher education,” Jewish Social Studies 12, 3 (Spring-Summer 2006): 157-192, page 159. [3] Andrew Grant, “The scientific exodus from Nazi Germany,” Physics Today, 26 September 2018. DOI:10.1063/PT.6.4.20180926a ; Michelle Borkin, Laurel Leff et al., “Rediscovering the Refugee Scholars of the Nazi Era,” https://www.northeastern.edu/refugeescholars/home [4] CIW Box 24, Charles B. Davenport Papers, Folder: Davenport, Charles Benedict, 1912-1917, Davenport to Professor. M. W. Blackman, State College of Forestry in Syracuse, March 24, 1914. Kornhauser’s his middle name was Isaac, and this wasn’t the last time he would run up against anti-semitism in his career. The fact that he was Jewish probably played a role in his being fired from a teaching position at Davidson College in 1922. Liz Rohan, “The historical construction of the ‘college man’ identity and World War I era archive of a Denison University fraternity man,” Oracle: The Research Journal of the Association of Fraternity/Sorority Advisors 11, 1 (Spring 2016): 36-45, page 41. His scientific career is summarized in H. J. Conn, “Sidney Isaac Kornhauser, 1887-1959,” Stain Technology 34, 3 (May 1959): 117. [5] Lamberti, “Reception of refugee scholars,” 179-182. [6] CIW Box 9, Folder: Blakeslee, A. F. 1938 (July-December) Meyer-Unger to Blakeslee, Dec. 18, 1938.