Cold Spring Harbor, NY — Life would be impossible if the DNA in dividing cells were replicated with anything less than near-perfect precision. Every time a nucleated cell commits to becoming two cells, every “letter” of its genome must be replicated once and only once. In humans, the task boggles the imagination. If unwound, the double helix crammed into each of our cells would measure 6 feet in length. In our bone marrow alone, half a billion new cells are born every minute. These cells alone contain enough DNA to wrap around the earth’s equator 25 times. Within daunting tolerances, each new cell must have a genome identical to that of the cell that gave birth to it. Cancer and other diseases can result when the process goes awry.

Figuring out how replication works at the level of individual molecules and atoms is one of the great achievements of modern science. The journey of investigators is not yet done, however. A major unsolved part of the puzzle is understanding how the entire process of copying the genome begins. In new research, insight into how the two stands of the double helix separate in the earliest stages of replication is becoming clear.

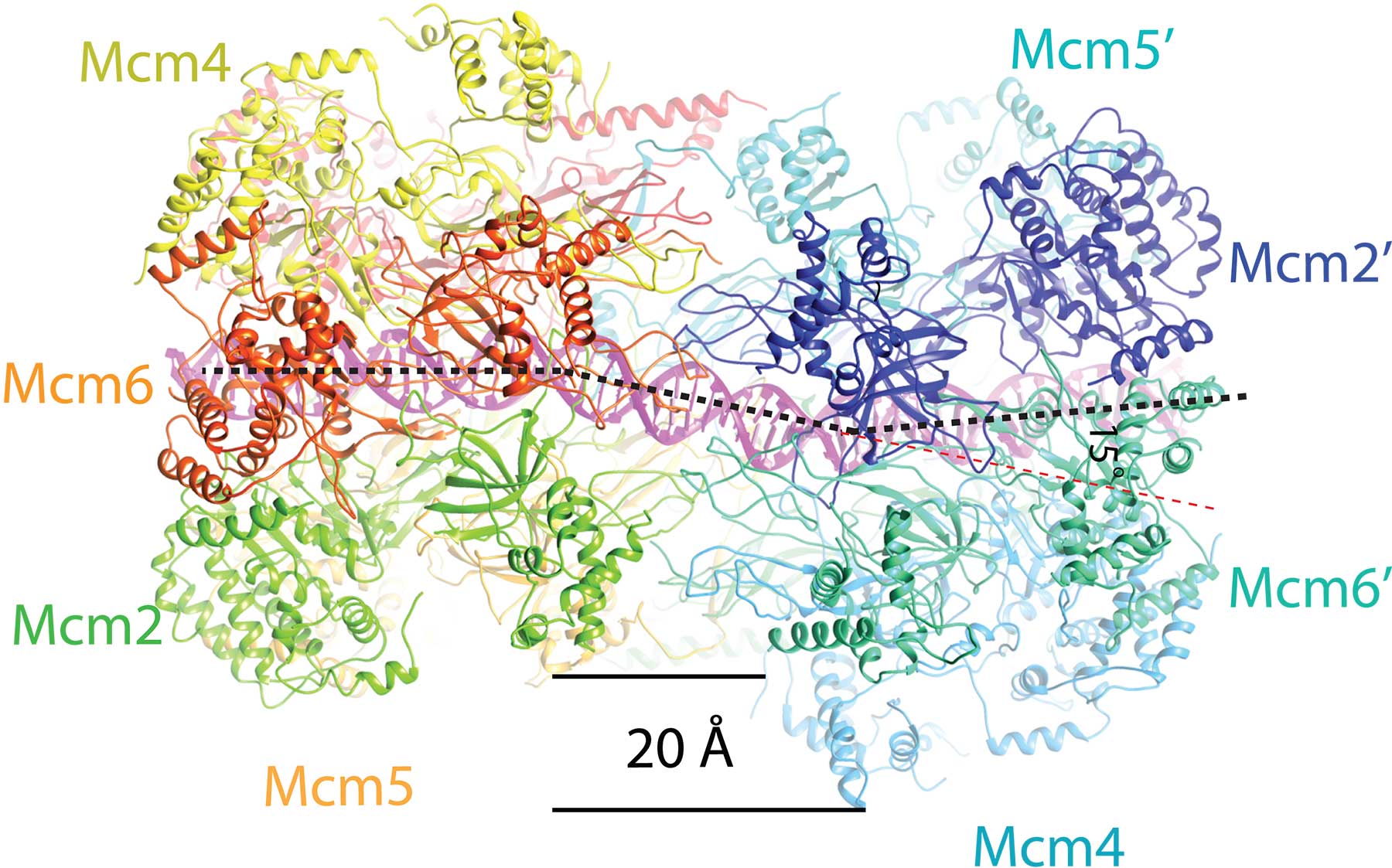

A longstanding collaboration by researchers in London, Grand Rapids, Michigan and Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory (CSHL) in New York reports the atomic-level structure of twin helicase enzymes loaded head to head, with the DNA double helix visible in the circular channel that runs though both helicases. The configuration, a part of what biologists call the pre-replicative complex (pre-RC), has never been successfully imaged in this configuration before.

The feat was made possible by a new cyro-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) facility at the Van Andel Research Institute, home of one of the lead investigators, Dr. Huilin Li. Dr. Li collaborated, among others, with Dr. Bruce Stillman of CSHL and Dr. Christian Speck, Professor of Genome Biochemistry and Molecular Biology at Imperial College in London.

A great deal of past effort has revealed how ORC assembles and finds replication “start sites.” The new research concerns what happens after the initial recognition of the start sites and how the DNA helix is unwound.

As vividly shown in the new cryo-EM “pictures,” the twin barrel-shaped helicase enzymes that surround the double helix look like symmetrical insects or, perhaps, twin spacecraft docked head to head. The question answered by the new structure is how the double helix is situated within the channel they form, and how DNA interacts with the surrounding structure. Based on that new knowledge, insight into how the two DNA strands separate, long a mystery, is beginning to be uncovered.

“The new images show that once loaded into the double hexamer—or DH, as we call the head-to-head helicases—the double helix takes a zig-zagging path through the central channel, which is sort of kinked,” the authors explain. “The two barrel-shaped hexamers are poised in such a manner that they are ready to untwist the double helix when activated.”

One consequence is especially important: the twist in the structure creates a tortional strain: the two hexamers load with an inherent tension that makes them something like a coiled spring. Details in the structure not previously seen reveal how various protein subunits of the twin hexamers latch on to the double helix, via tiny loop-like structures.

The scenario posited by Li, Speck, Stillman and their colleagues is that the structural tension causes one of the two strands of the DNA passing through them to literally bunch up against a closed “door” on one side of the ring, and the other strand against another closed “door” on the opposite side. The team proposes that one of the two doors springs open when the replication process inactivated (through the intervention of protein kinases and other helper molecules).

Through the open door in the helicase—but only on one side—one strand of the double helix is forced out, or “extruded.” The team proposes that it becomes what is called the “lagging strand” in the DNA replication process. The other strand, remaining in the center of the helical channel, becomes the “leading strand” in replication. Molecular motors loaded onto the two hexamers provide energy for their separation. One activated helicase passes the other, as replication of each strand proceeds in opposite directions, as deduced by biologists decades ago.

Written by: Peter Tarr, Senior Science Writer | publicaffairs@cshl.edu | 516-367-8455

Funding

This research was supported by the NIH, a UK Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council Grant, a Wellcome Trust Investigator Award, a UK Medical Research Council Grant and the Van Andel Research Institute.

Citation

Noguchi Y et al, “Cryo-EM structure of Mcm2-7 double hexamer on DNA suggests a lagging-strand DNA extrusion model” appears in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences the week of October 23, 2017.

About Van Andel Research Institute

Van Andel Institute (VAI) is an independent nonprofit biomedical research and science education organization committed to improving the health and enhancing the lives of current and future generations. Established by Jay and Betty Van Andel in 1996 in Grand Rapids, Michigan, VAI has grown into a premier research and educational institution that supports the work of more than 360 scientists, educators and staff. Van Andel Research Institute (VARI), VAI’s research division, is dedicated to determining the epigenetic, genetic, molecular and cellular origins of cancer, Parkinson’s and other diseases and translating those findings into effective therapies. The Institute’s scientists work in onsite laboratories and participate in collaborative partnerships that span the globe. Learn more about Van Andel Institute or donate by visiting www.vai.org. 100% To Research, Discovery & Hope®

About Imperial College

Imperial College London, founded in 1907, is the only UK university to focus entirely on science, engineering, medicine and business. Our international reputation for excellence in teaching and research sees us consistently rated in the top 10 universities worldwide. Generations of Imperial staff, alumni and students have changed the world with cutting-edge innovations; from the discovery of penicillin to the world’s first invisibility cloak. Recognition of this ground-breaking work has come in the form of 14 Nobel Prizes, 81 Fellowships from the Academy of Medical Sciences, 77 from the Royal Academy of Engineering and 73 from the Royal Society. For more information, visit www.imperial.ac.uk

Principal Investigator

Bruce Stillman

President and Chief Executive Officer

Oliver R. Grace Professor

Cancer Center Member

Ph.D., Australian National University, 1979