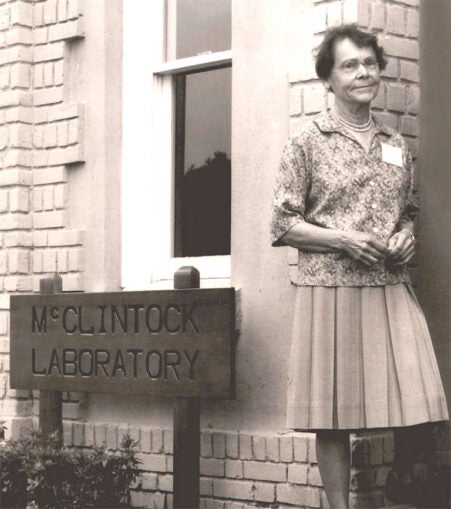

Barbara McClintock’s career at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory (CSHL) revolutionized genetics research. At CSHL’s “Animal House,” her groundbreaking experiments with corn led to the discovery of transposons, or “jumping genes” in 1944. Fifty years ago, at its 1973 Symposium, CSHL renamed the building in McClintock’s honor. Ten years later, in 1983, Barbara McClintock became the first woman to earn an unshared Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine.

It’s now known that transposons are widespread in plant and animal genomes. But this wasn’t always scientific consensus—far from it, in fact. When McClintock presented her research to the public in 1951, much of the science community dismissed it outright. “They said I was crazy—absolutely mad,” McClintock once recalled. “When you know you are right, you don’t care.” Later discoveries of transposons in fruit flies and yeast set the record straight. By the time she took a step back from active research in 1967, McClintock’s discoveries had gained broad acceptance.

Today, the McClintock Laboratory houses CSHL’s Amor Vegas, dos Santos, and Westcott labs. It is also home to Adjunct Associate Professor Sepideh Gholami. These four cancer researchers take on the disease from a variety of angles.

CSHL Fellow Corina Amor Vegas studies cellular senescence—when cells stop dividing but don’t die. Associate Professor Camila dos Santos researches how pregnancy affects breast cancer risk. Assistant Professor Peter Westcott focuses on how the immune system shapes tumor growth. Sepideh Gholami works to improve clinical trials and therapies for colorectal and liver cancer.

The Carnegie Institute of Washington, a predecessor of CSHL, built the “Animal House” in 1914. It is one of CSHL’s oldest buildings, a National Historic Landmark, and a beacon of inspiration for scientists both here in New York and all around the world.

Written by: Nick Wurm, Communications Specialist | wurm@cshl.edu | 516-367-5940