This Halloween, we’re casting our jack-o-lantern light on five of CSHL’s oldest buildings. So, come join us as we cross the threshold into the past.

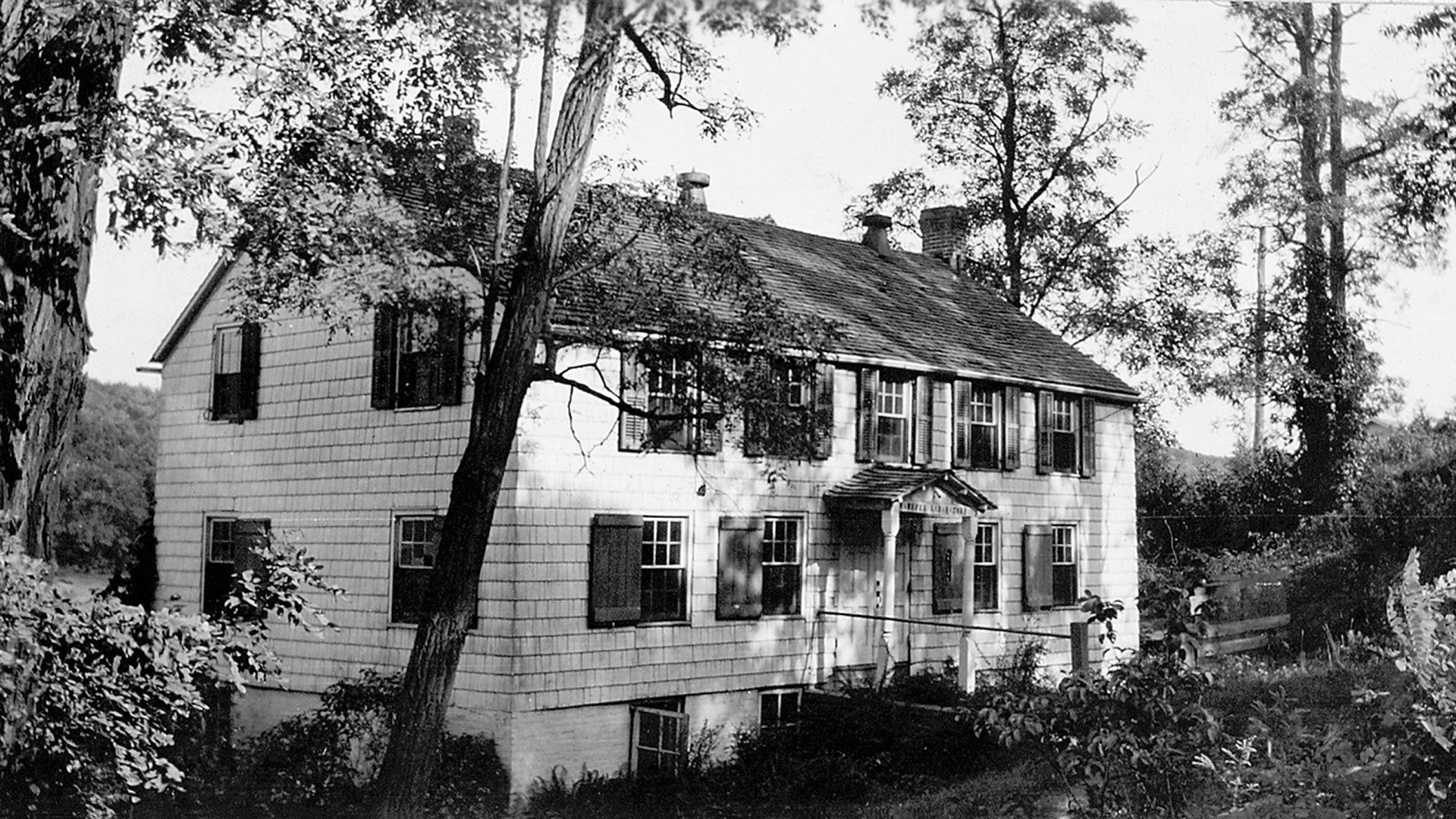

Jones Laboratory

Tales tell of a Welsh privateer who, after a life of high-seas adventure, settled on the south shore of Long Island. In time, his family would come to own thousands of acres stretching from Massapequa to Oyster Bay. His name lives on long after his passing. You may have heard of Jones Beach. Though the famous state park was named for Major Thomas Jones, it’s his great-great-grandson whose name graces CSHL’s oldest science building.

Jones Laboratory is the longest continuously operating research laboratory in the United States. This National Historic Landmark has stood virtually unchanged for over 130 years—at least on the outside. What began as the second home of CSHL’s earliest courses and education programs now houses the Lippman lab’s revolutionary plant genetics research. Over the years, Jones has withstood hurricanes, blizzards, floods, and more. But its bones are strong and today, this old soul remains as resilient as ever.

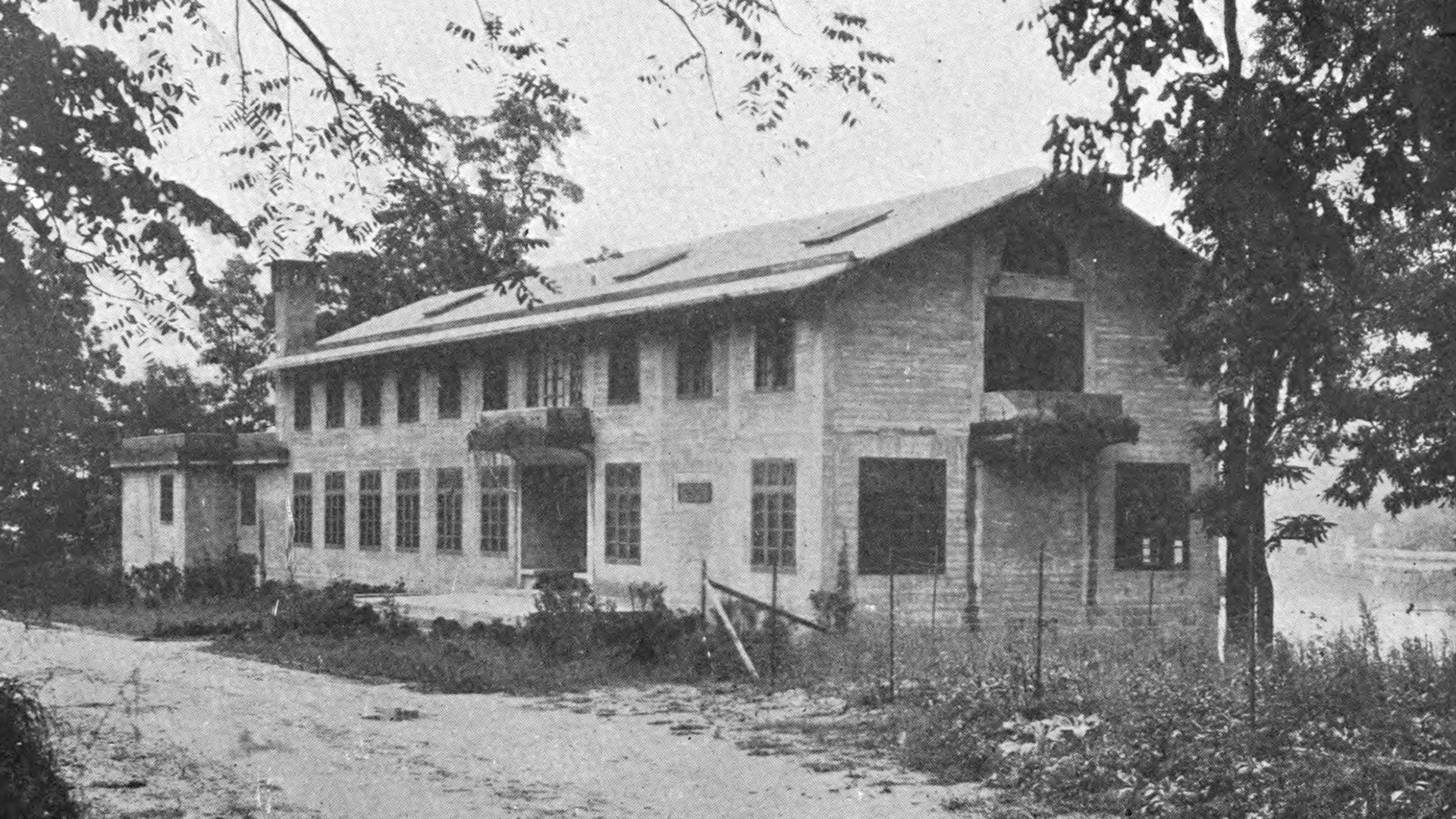

Carnegie Library

From 1890-1904, the Brooklyn Institute’s Biological Laboratory held the sole claim to science on the shores of Cold Spring Harbor. That changed at noon on June 11, 1904. Just south of Jones Laboratory, a new building and research organization opened along the shore. The Carnegie Institution of Washington’s Station for Experimental Evolution was “destined to be the leading center of biological research in the world,” according to the Brooklyn Institute’s W.H. Hooper.

Unlike the Biological Laboratory, the Station for Experimental Evolution primarily focused on research. Outside the building, botanist George Shull planted the crops he would later use to develop the first strains of “hybrid vigor” corn. Inside, the three-story building boasted rooms for breeding insects, birds, and aquatic animals, as well as research labs and a library.

Over the years, the Station’s main building would undergo several rounds of renovations. The breeding rooms were gone by 1911. In 1953, the research laboratories would follow. All that remained was the library. Since then, what was once a small collection of research texts has evolved into CSHL’s Library and Archives. The treasure trove of science history now contained within its walls includes, among other things, the personal collections of no fewer than five Nobel laureates.

Wawepex

Layers of history lurk beneath the unassuming facade of the Wawepex Building. Perhaps no other CSHL building can claim as many connections to the area. Its name comes from the original Native American settlement that stood at Cold Spring Harbor. Loose translations include “at the place of the good spring water” and “good little water place.” The Jones family’s Cold Spring Whaling Company constructed the building in the early 19th century to store barrels of whale oil. While in storage, these barrels would be plugged with bungs. Hence, even today the street passing through CSHL’s main campus bears the name Bungtown Road. Alas, all things must pass. The death of the whaling industry in the 1860s brought Jones’ company down with it.

In 1893, John D. Jones’ Wawepex Society leased the old storage building to the Biological Laboratory. Renovations replaced the warehouse with a dark room, lecture hall, operating room, and additional storage space. Wawepex has worn several masks since then. It’s been a dormitory, research building, administration offices, and even the headquarters of a children’s nature program. Today, it’s home to CSHL’s Office of Sponsored Programs. The Office plays a key role in facilitating and managing the grants and other funding avenues that make CSHL’s groundbreaking research possible.

Blackford Hall

By 1906, the Biological Laboratory’s curriculum included 10 courses and several specimen-collecting excursions. As useful as they were, Jones Laboratory and the Wawepex Building could no longer contain it all. As fate would have it, the widow of the Laboratory’s earliest benefactor, Eugene C. Blackford, would come to the rescue. Francis Blackford approached the Biological Laboratory that year with a “desire to erect a substantial building on the lands of the Laboratory … to provide a comfortable home for the faculty of the school and their families, and the young women pursuing courses of instruction or scientific research.”

Mrs. Blackford’s $25,000 donation—about $875,836 today—funded the design, construction, and furnishing of the new building. Blackford Hall, then the tallest building on campus, was dedicated in Eugene C. Blackford’s memory on June 1, 1907 (pdf). It was one of the first residential buildings built entirely of reinforced concrete. The main floor featured a dining room, meeting hall, and serving room. The second floor served as a women’s dormitory, and the basement contained a kitchen, laundry room, storage, and servants’ quarters. The first Symposiums on Quantitative Biology were held in Blackford before moving to Bush Lecture Hall in 1953 and then to Grace Auditorium in 1986.

Much has changed within Blackford Hall since 1907. Renovations have added more dining space and a basement bar. To this day, CSHL faculty, staff, students, and visitors continue to meet there to enjoy meals and talk science.

McClintock Laboratory

Today, this CSHL landmark bears the name of 1983 Nobel laureate Barbara McClintock. But McClintock was only 12 years old when the building opened in 1914. Before she walked its halls, and until it was renamed in her honor at the 1973 Symposium, the building was called the “Animal House.”

No, not that kind of animal house. You’d find no out-of-control frat parties there. Its original purpose was to be an animal breeding facility and, according to the 1911 Carnegie Institution annual report (pdf), to “relieve the main building (Carnegie Library) of the dirt that is inseparable from [its] culture.” By McClintock’s arrival in 1941, the breeding pens had been replaced by experimental labs. It was here that two of CSHL’s eight Nobel laureates—McClintock and 1969 winner Alfred Hershey—conducted their genetics research.

Today, the brick and stucco building is home to three CSHL Cancer Center members. Assistant Professor Katherine Alexander studies nuclear speckles and their role in gene regulation. Assistant Professor Corina Amor Vegas’ anti-aging research focuses on cellular senescence—when cells stop dividing but don’t die. Associate Professor Camila dos Santos investigates how pregnancy affects breast cancer risk. Their work has added to the building’s pedigree and to the legacies of their predecessors who once walked the same halls.