Passing down a healthy genome is a critical part of creating viable offspring. But what happens when you have harmful modifications in your genome that you don’t want to pass down? Baby plants have evolved a method to wipe the slate clean and reinstall only the modifications that they need to grow and develop. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory (CSHL) Professor & HHMI Investigator Rob Martienssen and his collaborators, Jean-Sébastien Parent and Institut de Recherche pour le Développement Université de Montpellier scientist Daniel Grimanelli, discovered one of the genes responsible for reinstalling modifications in a baby plant’s genome.

A plant’s genomic modifications—called epigenetic modifications—help turn off genes at the right times. Epigenetic changes accumulate with age. Martienssen explains:

“If you think about a tree, the flowers that arise a hundred years after it germinated, they’re obviously a long way from the original acorn, and an awful lot of epigenetic changes could happen in that period. And so, these are important resets for development so that you don’t inherit this epigenetic collateral damage.”

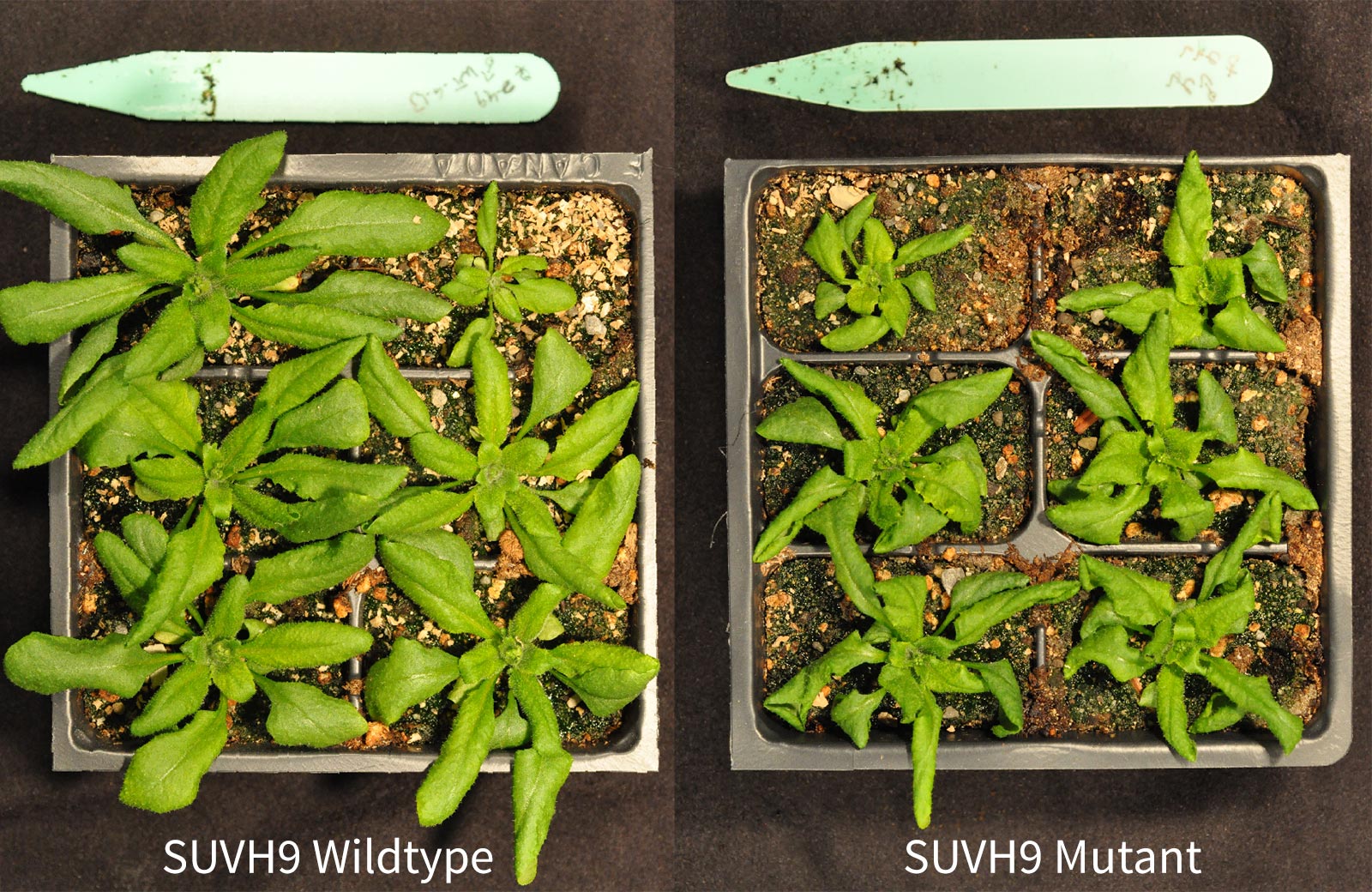

Martienssen’s team discovered that after baby plants remove the epigenetic modifications, the SUVH9 protein puts back the ones they need to survive. Without SUVH9, plants develop poorly because the wrong genes turn on at the wrong time. Parent, a research scientist at Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada, says:

“I remember this moment where we were like, ‘Wow! This is not what we expected.’ There was an opening for an actor that was not accounted for in the standard models, and that was the most innovative part of our story.”

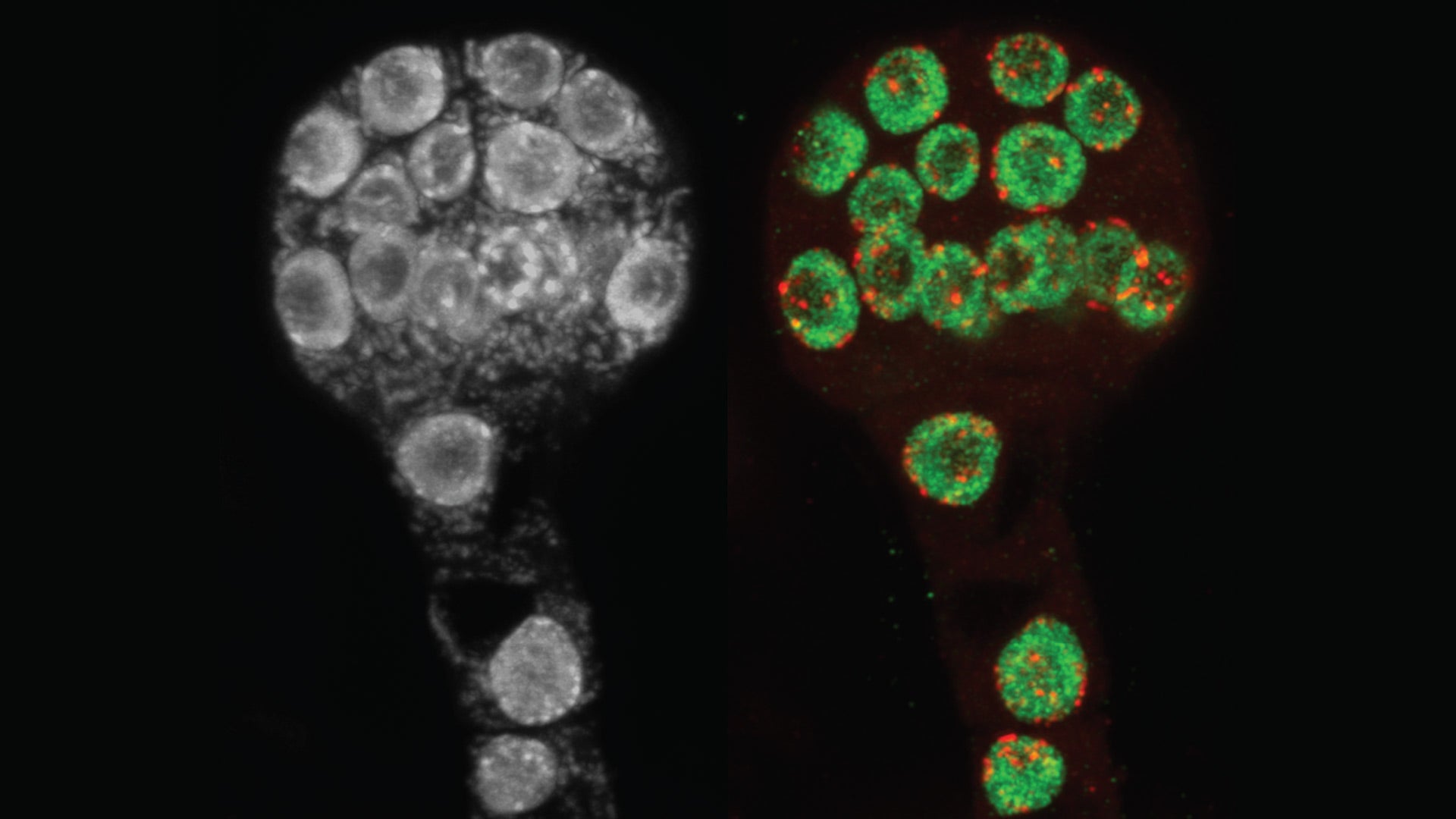

The SUVH9 protein uses small snippets of RNA to look for the right places to reinstall the beneficial modifications, which are on mobile genetic elements known as transposons. The SUVH9 protein adds the epigenetic modifications to them, and this ensures nearby genes are turned off at the right time. Reinstalling the beneficial modifications also stops the transposons from jumping around in the genome and disrupting other genes.

The scientists think SUVH9 protein contributed to today’s plant diversity. By stopping harmful transposons from disrupting genes, the protein allowed different species to evolve. Parent says:

“One of the big mysteries about flowering plants is how they manage to become so diverse and to generate so many different species so quickly in evolutionary history. And, we believe that we are touching here a part of a molecular mechanism that can allow this sort of flexibility.”

Written by: Luis Sandoval, Communications Specialist | sandova@cshl.edu | 516-367-6826

Funding

The Howard Hughes Medical Institute, the National Institutes of Health, the National Science Foundation Plant Genome Research Program, the Agence Nationale de la Recherche, CHROMOBREED, Marie Skłodowska-Curie actions, Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Shared Resources, and the CSHL Cancer Center

Citation

Parent, J-S., et al., “Small RNAs guide histone methylation in Arabidopsis embryos”, Genes and Development, May 20, 2021. DOI: 10.1101/gad.343871.120

Principal Investigator

Rob Martienssen

Professor & HHMI Investigator

William J. Matheson Professor

Cancer Center Member

Ph.D., Cambridge University, 1986