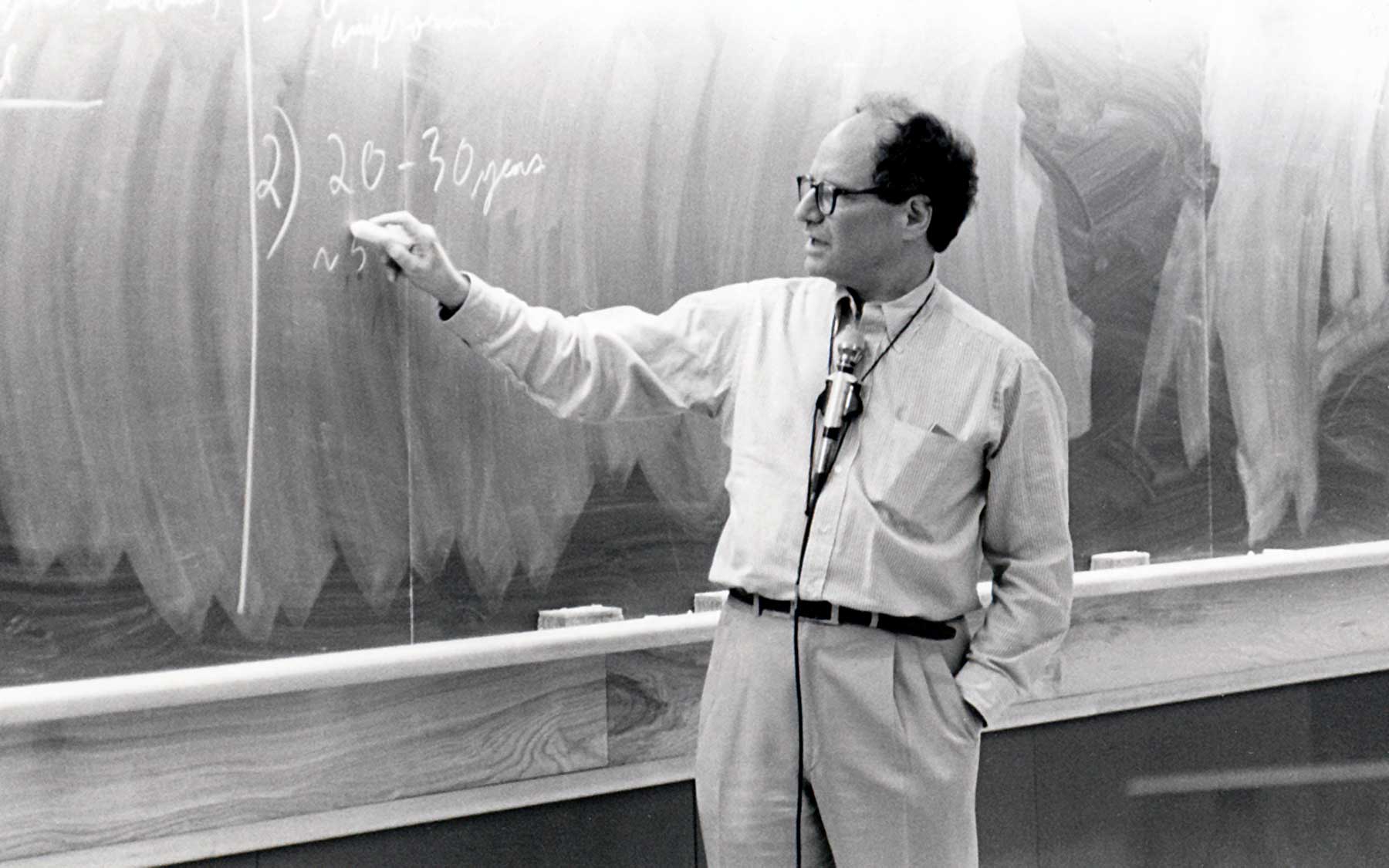

“It was very divisive, a lot of people said no, it’s just too big, too boring, the time hasn’t come,” Watson remembers in this brief video. “At that time we had some viral DNAs, we had about 100,000 [DNA base pairs]. When you talked about [sequencing] humans it was a 10,000 times bigger project.”

The idea had gained momentum throughout the late 1980s at meetings first held in 1986 at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, where the value of basic science has always been stressed. But even CSHL scientists could not have predicted just how big a win for basic science the Human Genome Project (HGP) would become.

While the hesitation about the project was far from unfounded considering that it was a $3.8 billion effort, that investment turned out to be the best bargain in biology, and possibly any science, to date. In the first 20 years following its launch, the Human Genome Project generated $796 billion in economic activity in the US, according to a 2011 report (pdf) by the Battelle Memorial Institute.

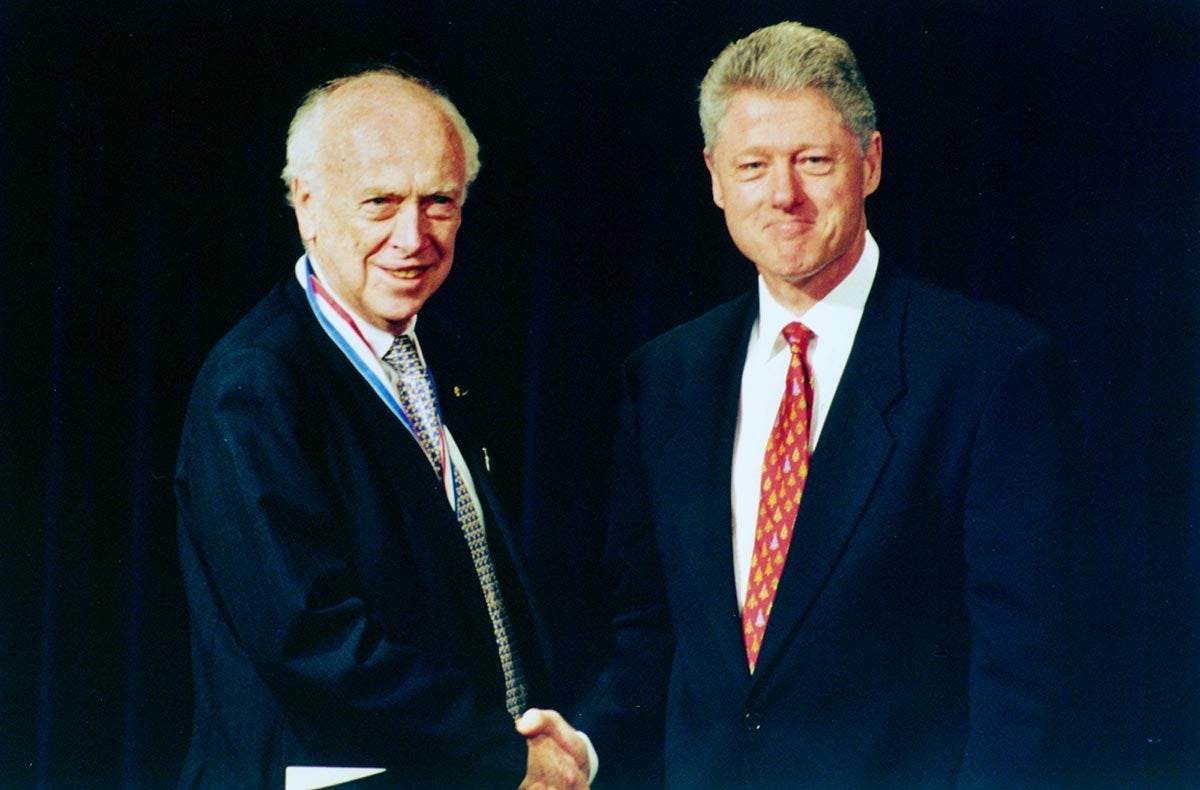

Impressive as those numbers may be, dollars are still an inadequate measurement of the Human Genome Project’s value. It also “initiated a new way of doing science,” as Jim Watson, National Human Genome Research Institute Director Eric Green, and NIH Director Francis Collins put it in a piece published this week in Nature, reflecting on the HGP’s silver anniversary.

Learn how CSHL served as a crossroads for scientists involved in the HGP

The HGP is where biology went big. It represents the first truly large-scale collaborative project in biology. A multitude of consortium-based research efforts, most recently the President’s BRAIN initiative, have since followed in its wake. The mammoth datasets that sequencing projects are producing have ironically generated a new set of problems, albeit ones that are good to have. Some scientists, including CSHL’s quantitative biologist Mike Schatz, have recently wondered whether we will soon be using the word ‘genomical’ in place of ‘astronomical’ to describe things that are really huge.

But perhaps Watson described it best, back at the beginning, when the Human Genome Project was little more than a twinkle in the eyes of a few prescient scientists. To them, whether or not the project should be undertaken was never a question. Watson predicted in CSHL’s 1986 annual report: “To [human geneticists], the possession of the complete human DNA sequence would be a resource of inestimable value. To have it within our grasp and not go for it strikes them as an act of gross irresponsibility to society.”