In honor of National Cancer Research Month, we welcome guest blogger Miriam Fein, a Stony Brook University graduate student who is working in Assistant Professor Mikala Egeblad’s Lab here at CSHL.

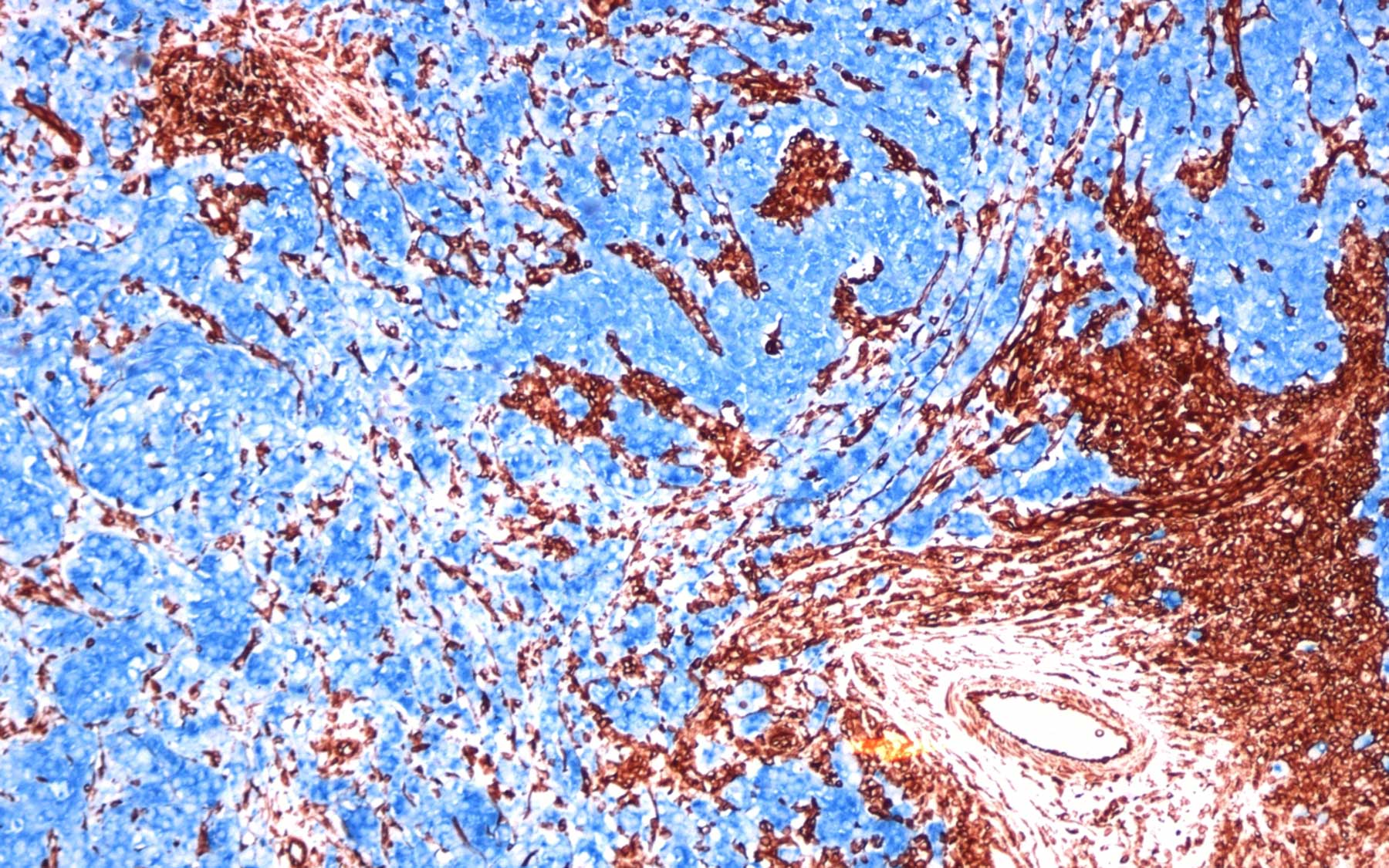

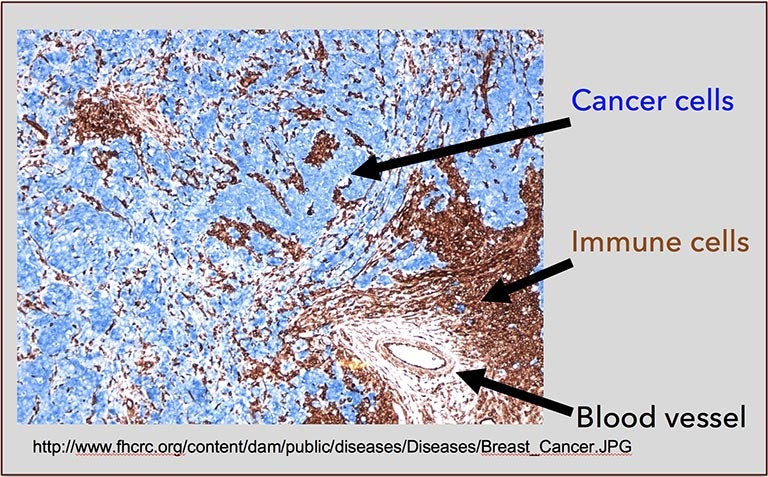

When you are looking for a place to live, the neighborhood matters a lot. Good schools, affordable housing, low crime rate, and of course, great neighbors. Neighbors provide support—a cup of sugar when you are low, a helping hand to feed the cat when you are away—that makes life easier.The same principle applies in the body. Cells within a ‘neighborhood’ support one another. Immune cells protect their neighbors from infection and blood vessels deliver nutrients and oxygen to the region. A matrix made of fibers and proteins provides structure and support to the surrounding cells.

And yet, these same “friendly neighbors” can be a significant problem when it comes to cancer: healthy cells in a tumor’s neighborhood can actually promote cancer growth.

For scientists, a tumor’s neighborhood is known as its “microenvironment.” Over the last few decades, research has shown that the tumor microenvironment supports cancer growth and metastasis.

I’m a member of Dr. Mikala Egeblad’s lab here at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory. We are working to identify new drugs that target the tumor microenvironment. Our hope is that these new treatments can be used in concert with standard chemotherapies—and the combination will be more effective than targeting tumor cells alone.

Dr. Egeblad recently sat down with editors of the scientific journal Cancer Discovery to discuss her research on the tumor microenvironment. As she explained in that interview, the cells surrounding a tumor have the capacity to slow down tumor growth. But what has been most surprising is that the tumor sends out signals that push these healthy neighbors to promote cancer growth instead of attacking the tumor. Even worse, the healthy neighbors surrounding a tumor can send signals back to the cancer that enable tumor cells to become resistant to therapy.

When tumors are treated with certain chemotherapy drugs (which target fast-growing tumor cells), immune cells in the neighborhood respond by sending out survival signals or signals that encourage new blood vessels to form. Both enable the tumor to grow faster and promote metastasis.

There are so many unanswered questions facing cancer researchers now. For example, why is metastatic breast cancer so hard to treat? Is it because of new mutations in the metastasized tumor or is the microenvironment playing an even bigger role? Can we reverse the signals provided by cells in the neighborhood after chemotherapeutic treatments?

Cancer researchers are now employing several approaches to target the microenvironment. We are trying to prevent certain types of immune cells from entering the tumor in the first place. We are also targeting the signals that healthy neighbor cells release to promote tumor growth. Current early-stage clinical trials look promising. Scientists are also having a great deal of success using immunotherapy—treatments that use the body’s own immune system to target cancer.

Much of this research is possible because of a cutting-edge new imaging technique, known as intravital imaging. It’s a way of imaging of living mice at a microscopic level. The method, which was highlighted this month in a story in Nature that also discusses Dr. Egeblad’s work, allows us to understand how cancer cells behave. We can see how tumor cells invade blood vessels, and where and when various signals are turned on and off. We are able to watch the interaction between tumor cells and their healthy neighbors. These powerful tools may be the key to understanding how the microenvironment supports—and find novel ways to prevent—cancer growth.

For more on Dr. Egeblad’s work, see her recent public lecture, or follow her on Facebook and Twitter.