Recent findings in pancreatic cancer research demonstrate that antioxidants aren’t exactly the reliable guardians that they’re often made out to be in health food ads. Researcher and practicing cancer doctor David Tuveson explains how this fits into what scientists have learned about the connection between antioxidants and cancer.

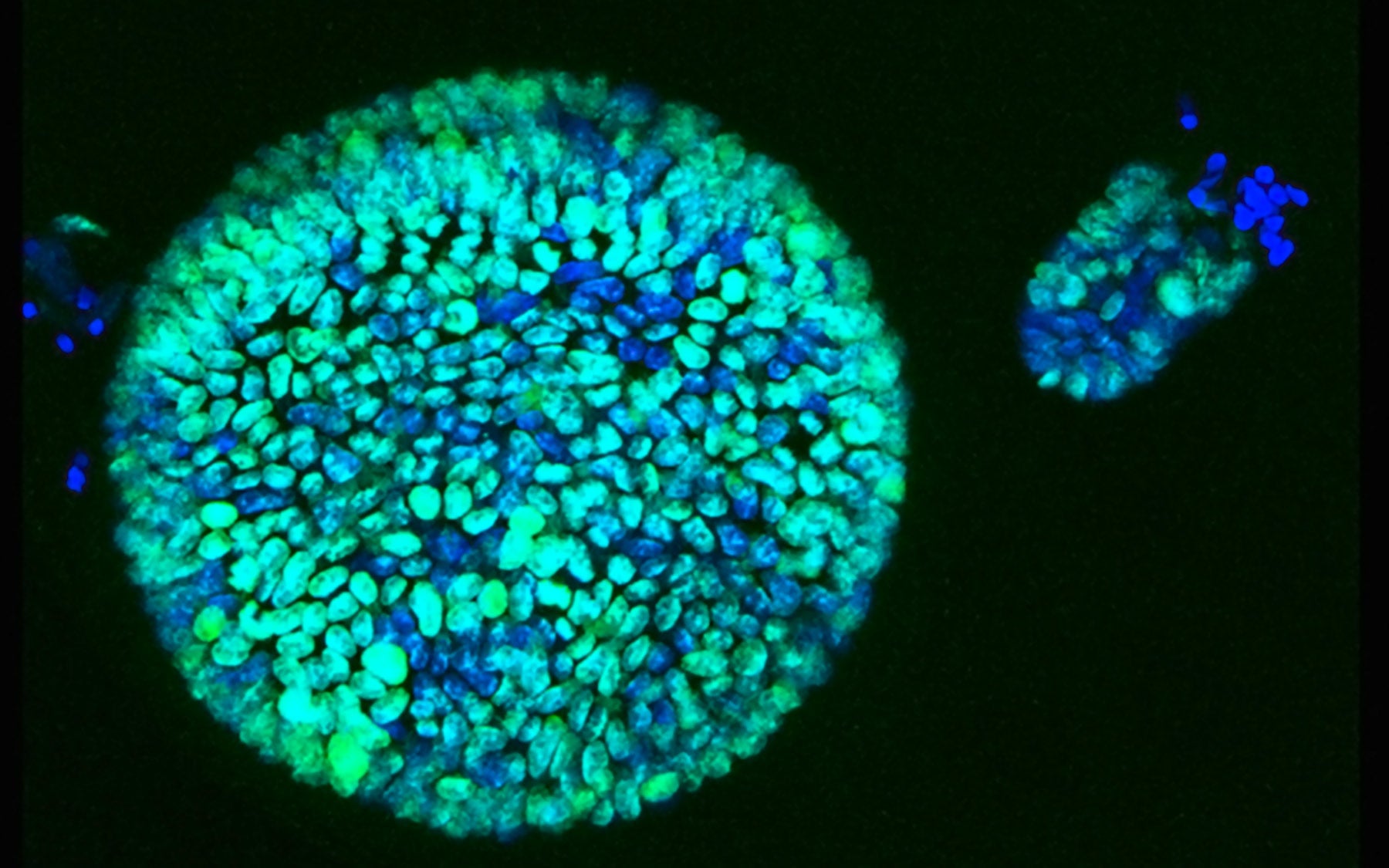

Advertisements for products like pomegranate juice tell us that antioxidants can help us be “crazy healthy.” Maybe you’ve heard about how they neutralize “cancer-causing free radicals.” But what does the science tell us about the connection between antioxidants and cancer? And perhaps more importantly, what doesn’t it tell us?The results of a recent study from the lab of CSHL Professor David Tuveson are part of a growing body of evidence that for cancer patients, antioxidants may not be the “reliable guardians” they’re made out to be in the video below. Experiments on pancreas organoids—models that are essentially balls of cells sampled from the pancreas of healthy people and pancreatic cancer patients—showed that lowering antioxidant levels within cancerous pancreas cells, or cells on the way to becoming cancerous, kills them. (The finding does not apply in healthy pancreas cells.)

Tuveson, who is a practicing cancer doctor as well as a renowned researcher, says that you can trace the idea that antioxidants ward off cancer all the way back to famed chemist Linus Pauling, who wrote a book on it in 1979. He came up with this idea largely based on clinical trials that showed cancer patients who received intravenous (IV) vitamin C, a well-known antioxidant, fared better than those who didn’t.

Read more in the Wall Street Journal about David Tuveson’s role in the field of pancreatic cancer.

We usually don’t get our vitamin C by pumping massive quantities into our veins, of course. In the nearly 40 years since Pauling wrote his book Cancer and Vitamin C, scientists have learned that unlike when you eat vitamin C, when it enters the body via IV a chemical reaction occurs that turns this antioxidant into an oxidant—and oxidants are the source of those free radicals that antioxidants “annihilate.”

Why would oxidants help cancer patients when it’s their arch nemeses, antioxidants, that are supposed to improve health? Many people “think there’s only a good and a bad to oxidation: oxidation is bad, antioxidation must therefore be good,” says Tuveson, but “it’s more complicated than that.” Ads for “health foods,” like the one above, often play upon this popular but false dichotomy.

The truth is, we need reactive oxygen—a type of oxidant, and therefore a source of free radicals—in order to live. Tuveson explains that reactive oxygen is essential in a variety of bodily processes. It helps ensure that our cells manufacture proteins properly. Our immune system uses it to kill invaders. And it’s part of our cells’ signaling systems.

It’s true that too much of an oxidant like reactive oxygen can wreak havoc. “Oxidants damage things, they age your body, they damage your DNA,” says Tuveson, and this damage can give rise to cancer. But, “a little bit of reactive oxygen in otherwise normal cells is very health-beneficial,” he adds.

The key words there are “in otherwise normal cells.” According to Tuveson, “it turns out the scaredy cat in this whole situation is the cancer cell, which cannot deal with reactive oxygen and really waves the white flag when you raise reactive oxygen.” Many chemotherapy drugs and radiation treatments actually kill cancer cells in part by raising levels of reactive oxygen.

Click the orange “play” button to hear from researchers in David Tuveson’s lab in an episode of CSHL’s Base Pairs podcast. The image shows organoids (blue) grown from pancreas cells.

Healthy cells maintain a fine balance of antioxidants and oxidants. When cells divide, they make a lot of reactive oxygen, because making new cells involves many of those processes for which reactive oxygen is essential. Following division, cells then use antioxidants to neutralize the excess reactive oxygen. “Cancer cells divide a lot, so they make a lot,” Tuveson explains. “And therefore they need to reduce that level way down” using antioxidants. They must restore the balance in order to keep growing.

In that recent study from Tuveson’s lab, researchers used pancreas organoids to figure out whether they could kill cancer cells, while leaving nearby healthy cells undamaged, by reducing antioxidant levels. This is called synthetic lethality: discovering conditions that are harmful to cancer cells but not healthy cells. It’s an enormous challenge in cancer research—think about how harmful chemotherapy is.

Based on the encouraging results of this study in organoids, lowering antioxidant levels within cancer cells could be one way to do this. This does not tell us the effect that eating antioxidant-rich foods has on cancer, however. That remains an active area of research with many unanswered questions.

This is why the Linus Pauling case is so important. When he wrote that book, no one had shown that taking vitamin C orally would have those same cancer-killing effects observed when it was administered by IV—in fact, taking lots of vitamin C orally can harm health. But the paper from Tuveson’s lab does tell us that when antioxidants make it into cancer cells, they can make a bad situation worse.

P.S. It’s only tangentially related to the topic explored above, but here’s the number one thing that Tuveson wishes people knew about antioxidants: “Just don’t have your fruit juice until two hours after exercise. It turns out that if you give people antioxidants around the time that they exercise, which can be as simple as a big glass of orange juice, you neutralize the positive benefits of exercise.” It has to do with antioxidants’ involvement in cell signaling—the way cells communicate with each other—and their resulting ability to regulate the blood sugar.