Robert Maki, M.D., Ph.D., has been determined to eliminate what he calls the “guessing game” aspect of cancer treatment from the very start of his more than 20-year career as a medical oncologist. His goal was “not just to practice medicine, but also to learn more about the ‘why’ part of medical problems.” With the help of new technologies such as three-dimensional cellular models, he and CSHL scientists are now working together to find those “whys” so that he can give patients effective treatments from the outset.

In addition to being an internationally renowned physician specializing in sarcoma—cancers that arise in bones and connective tissues—Maki is a CSHL professor, member of CSHL’s NCI-designated Cancer Center and the director of the Center for New Cancer Therapies (CNCT) at the Northwell Health Cancer Institute. Straddling these two institutions gives him the perspective he needs to bring cancer research closer to the practice of treating patients. He is one of the leaders of a strategic affiliation between CSHL and Northwell, established in 2015 with the goal of increasing cutting-edge treatment options for patients throughout the healthcare system.

It has become routine for Maki to be in the clinic treating cancer patients one day, and soaking up the very latest cancer research discoveries in one of CSHL’s conference rooms the next. But he notes that as much as he serves as a human bridge between lab bench and bedside, the patients themselves provide the most direct link. Through the affiliation, scientists at CSHL have already received tissue samples from 140 Northwell patients. These invaluable samples are helping researchers pinpoint weaknesses in cancer that they can target with both new and existing drugs.

Fostering exchanges between different areas of science has been part of Maki’s approach since his days as an undergraduate in Northwestern University’s Integrated Science Program. He found the widening intersection between biochemistry and medicine particularly alluring. It opened up opportunities to discover the “whys” he craved, by revealing how diseases work at a molecular level.

When it came time to move on to medical school, Maki decided he must pursue scientific research alongside his clinical training, opting for an M.D.-Ph.D. program at Weill Cornell, in connection with Sloan Kettering. “I could see that there were going to be dramatic changes during my lifetime in terms of the understanding and treatment of cancer,” he says. He was right.

Scientists were making major discoveries about cancer’s inner workings while Maki was going through college and medical training in the 1980’s and early 1990s. The 1982 discovery of the first human cancer gene, which happened right here at CSHL in the lab of Professor Michael Wigler, was a huge step toward today’s concept of cancer as a complex amalgam of genetic damage. But that was only the beginning.

Today, Maki is working directly with trailblazing CSHL scientists who are revealing the molecular-level tricks behind cancer’s sinister survival skills, and building a program to translate those discoveries into more precisely targeted therapies. “Unless you deeply understand how and why something functions, at best you are making guesses as to what will be useful. Until now, oncology has largely been a field based on serendipity and bootstrapping.” Maki says. “The work of the Laboratory is absolutely critical in understanding exactly how cancer cells both grow and survive despite the poisons that we throw at them.”

Innovation in 3D

At the heart of Maki’s quest for the “whys” behind cancer is the question: why do treatments that work for one patient sometimes fail to help another patient with the same type of cancer? The jungle of genetic abnormalities that is characteristic of cancer cells undoubtedly holds some answers. Yet traditional cells-in-a-dish systems for cancer research can intensify the genetic thicket, spurring even more mutations within cancer cells as they adapt to the foreign environment of a flat piece of plastic. And healthy cells are not resilient enough to survive in a dish at all, which leaves scientists without a key point of comparison.

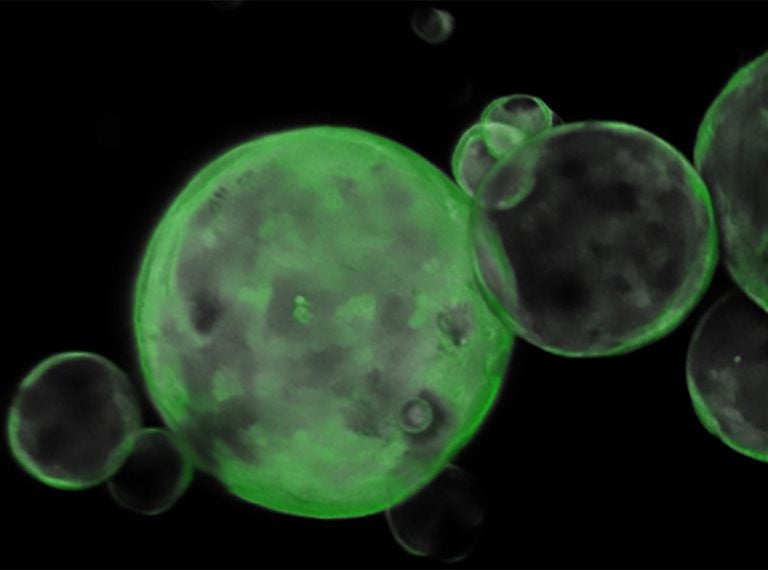

Fortunately, Dr. David Tuveson, CSHL Cancer Center Director and Professor, is one of the pioneers of a new, three-dimensional cell-culture system that much more closely mimics conditions in the body. Maki sees this new system, which generates spherical balls of cells called organoids, as being central to building a relationship between the labs and the clinic where “one informs the other.” Infrastructure is now in place to quickly transport both healthy and cancerous tissue samples from Northwell patients to CSHL so that scientists can grow them into organoids for experimentation.

The organoid system offers two enormous advantages, Maki explains. First, it allows scientists to grow healthy and cancerous cells in the lab side-by-side, providing an invaluable asset in the search for new targets for therapy. Maki highlights work from the lab of Director of Research and Professor David Spector as a prime example. Spector’s team is creating a biobank of patient-derived breast organoids in collaboration with the Northwell Health Tissue Donation Program. By comparing the DNA sequences and the activity of various genes between healthy and cancerous organoids, they aim to identify genes that drive cancer and ways to disarm them with new treatments.

Scientists from Professor David Tuveson’s lab used organoids to show how antioxidants may actually help cancer cells survive. Learn more in this episode of CSHL’s Base Pairs podcast.

Meanwhile, organoids also present opportunities for cancer doctors like Maki to test existing treatments on organoids first, since organoids can model a specific patient’s tumor. “The idea,” Maki explains, “is to take a sample of tumor, grow it for several weeks as organoids, and then treat the organoids with different medications to see if one of those might work best.” He hopes that through this process, organoids “may give us a tool to help choose treatments more effectively for patients.”

Bridge to better treatments

Several of the translational research projects bolstered by CSHL’s strategic affiliation with Northwell Health are closing in on precise new targets for treatment, much to Maki’s delight. The Spector lab is using the organoid biobank they built to evaluate potential new breast cancer therapies that target lncRNAs, which are molecules closely related to DNA. Taking a completely different approach, Associate Professor Mikala Egeblad’s team is working on a way to prevent the spread, or metastasis, of breast cancer using drug-coated nanoparticles.

While these innovative strategies harness CSHL scientists’ world-class expertise in molecular biology, scientists alone cannot get a new potential treatment ready for use in patients. They must work with clinicians. Maki will streamline that process for CSHL scientists as the leader of a Phase 1 Experimental Therapeutics Unit at Northwell, a first step in the clinical trials process. There, “our job is to find out if these medications can be given safely,” he says. “It’s through this kind of a mechanism that we’re able to improve upon standards of care as they exist for cancer therapy as of 2018.”

Maki now has another internationally recognized cancer doctor and clinical researcher on his team as he guides the translation of innovations from CSHL labs to the clinic. Richard Barakat was appointed in early 2018 to serve as physician-in-chief and director of the Northwell Health Cancer Institute and will work closely with Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory as part the strategic affiliation. “He’s coming at an ideal time,” says Maki, “to help us to increase the number and types of projects that we do together to understand cancer better, and to provide better treatments for our patients.”

As the pipeline of translational research continues to grow, Maki emphasizes that it is “paramount that we bring fresh blood into the fight against cancer, and there’s no greater investment that we can make than in young people.” Students finishing their internal medicine residency can now apply for a fellowship where they focus on the clinic at Northwell, and then spend two years at CSHL to pursue their research interests. The first fellow in the Northwell Health and CSHL Joint Fellowship in Clinical Medical Oncology and Laboratory Investigation program has already been selected and will start in July 2018. When Maki speaks about training the next generation of clinician-scientists, you can hear the smile in his voice.

For Maki, this merging of worlds is a rewarding reflection of the approach he has always had toward fighting cancer. “It’s an exciting time for cancer research on Long Island,” he says, “and it just makes perfect sense for these two strong institutions to work together to better understand and better treat cancer.”

Written by: Andrea Alfano, Content Developer/Communicator | publicaffairs@cshl.edu | 516-367-8455