Some basic biology learned from study of fruit flies could help us understand food choice in obese people.

Cold Spring Harbor, NY — Think of the smell of freshly baking bread. There is something in that smell, without any other cues—visual or tactile—that steers you toward the bakery. On the flip side, there may be a smell, for instance that of fresh fish, that may not appeal to you. If you haven’t eaten a morsel of food in three days, of course, a fishy odor might seem a good deal more attractive.

How, then, does this work? What underlying biological mechanisms account for our seemingly instant, almost unconscious ability to determine how attractive (or repulsive) a particular smell is? It’s a very important question for scientists who are trying to address the increasingly acute problem of obesity: we need to understand much better than we now do the biological processes underlying food selection and preferences.

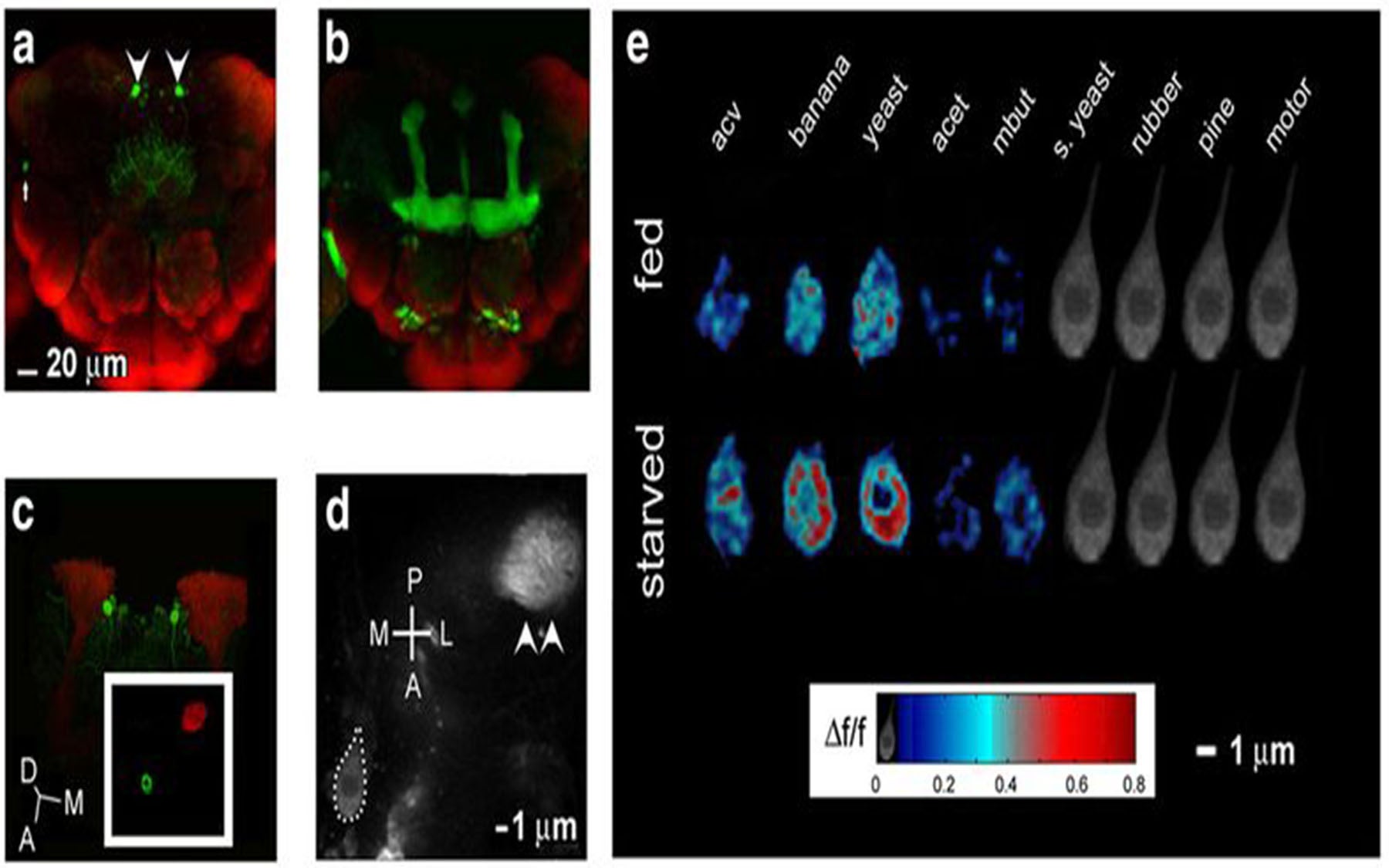

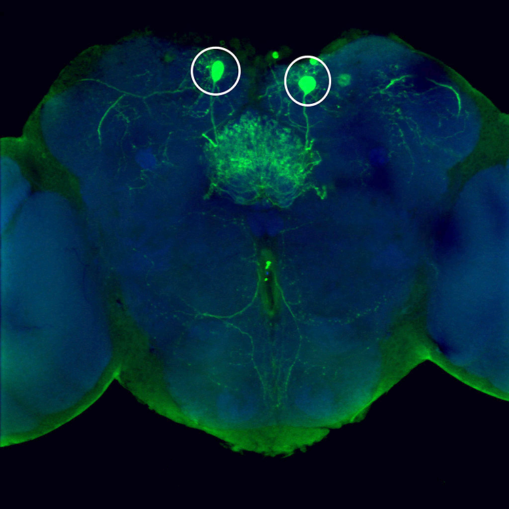

New research by neuroscientists at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory (CSHL), published in The Journal of Neuroscience, reveals a set of cells in the fruit fly brain that respond specifically to food odors. Remarkably, the team finds that the degree to which these neurons respond when the fly is presented different food odors—apple, mango, banana—predicts “incredibly well how much the flies will ‘like’ a given odor,” says the lead author of the research paper, Jennifer Beshel, Ph.D., a postdoctoral investigator in the laboratory of CSHL Professor Yi Zhong, Ph.D.

“We all know that we behave differently to different foods—have different preferences. And we also all know that we behave differently to foods when we are hungry,” explains Dr. Beshel. “Dr. Zhong and I wanted to find the part of the brain that might be responsible for these types of behavior. Is there somewhere in the brain that deals with food odors in particular? How does brain activity change when we are hungry? Can we manipulate such a brain area and change behavior?”

When Beshel and Zhong examined the response of neurons expressing a peptide called dNPF to a range of odors, they saw that they only responded to food odors. (dNPF is the fly analog of appetite-inducing Neuropeptide Y, found in people.) Moreover, the neurons responded more to these same food odors when flies were hungry. The amplitude of their response could in fact predict with great accuracy how much the flies would like a given food odor—i.e., move toward it; the scientists needed simply to look at the responses of the dNPF-expressing neurons.

When they “switched off” these neurons, the researchers were able to make flies treat their most favored odor as if it were just air. Conversely, if they remotely turned these neurons “on,” they could make flies suddenly approach odors they previously had tried to avoid.

As Dr. Beshel explains: “The more general idea is that there are areas in the brain that might be specifically involved in saying: ‘This is great, I should really approach this.’ The activity of neurons in other areas in the brain might only take note of what something is—is it apple? fish?—without registering or ascribing to it any particular value, whether about its intrinsic desirability or its attractiveness at a given moment.

Written by: Peter Tarr, Senior Science Writer | publicaffairs@cshl.edu | 516-367-8455

Citation

“Graded Encoding of Food Odor Value in the Drosophila Brain” is published in The Journal of Neuroscience. The authors are Jennifer Beshel and Yi Zhong. The paper can be viewed at: http://www.jneurosci.org/content/33/40/15693.full?sid=95f7a9b6-f6bf-4875-9b64-7cd2dab41705